When our ancestors developed the various forms of cultured or fermented food and beverages, they had no idea of beneficial enzymes or bacteria, or of the enhanced vitamin content they were getting from these products. Their main concerns would have been the flavour and keeping-quality. Over time these foods rose to importance to them for their many health benefits. Scientific research was not conducted to attest to the validity of the foods, it was a hit and miss affair with experience being the guide. Today, soy sauce, sauerkraut, yoghurt and sour dough bread are just a few of the cultured foods that are respected world wide.

When our ancestors developed the various forms of cultured or fermented food and beverages, they had no idea of beneficial enzymes or bacteria, or of the enhanced vitamin content they were getting from these products. Their main concerns would have been the flavour and keeping-quality. Over time these foods rose to importance to them for their many health benefits. Scientific research was not conducted to attest to the validity of the foods, it was a hit and miss affair with experience being the guide. Today, soy sauce, sauerkraut, yoghurt and sour dough bread are just a few of the cultured foods that are respected world wide.

According to Japanese mythology, miso, fermented from soy beans and other legumes, was a gift to mankind from the gods. Miso is a rich source of nutrients, especially B vitamins, lactic acid bacteria and digestive enzymes which contribute to intestinal health. Miso is higher in vitamins B2, B3 and B12 than non-fermented soy beans.

In The Book of Miso there are many cases of people who consumed miso daily being able to withstand the effects of atomic radiation. Dr Akizuki worked closely with fallout victims for 2 years after the blast. He attributed his immunity to radiation sickness to his daily bowl of miso soup. His diet and that of his co-workers consisted of brown rice and miso soup and none of them suffered any ill-effects of radiation. Dr Akizuki wrote: “I think miso soup is the most important part of one’s diet … Mothers complaining about their children’s illnesses, when asked whether or not they give their family miso soup, invariably say no … the family that is rarely sick always takes miso soup every day, without exception. However, miso soup is not a drug … it does not cure sickness right away. If you are taking it daily, your constitution improves and you acquire resistance to sickness … miso is an agent which brings out the value of all food. And it more easily allows the body to assimilate its food.”

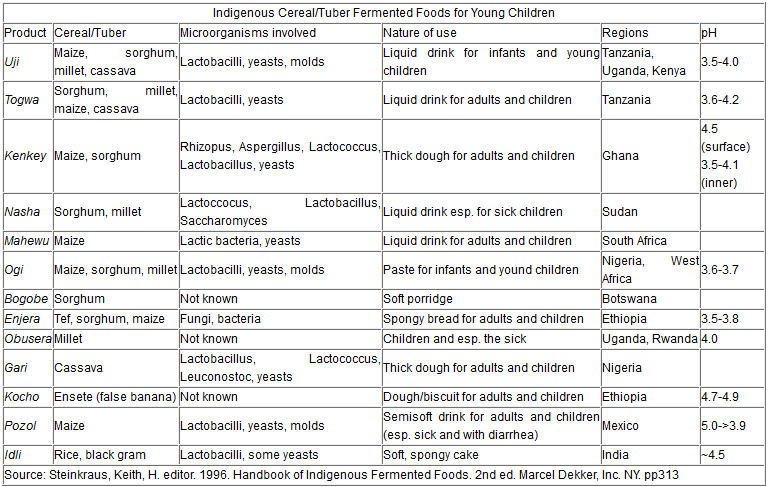

Another traditional food, akamu or uji as it is most commonly known in Eastern Africa, is a suspension of maize, millet, sorghum, or cassava flour in water. It is either fermented before or after cooking or is cooked fresh to make a creamy soup. Uji is consumed widely in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. It is used as a weaning food, thirst-quenching drink, or side dish, and it is believed by some to enhance lactation.

Uji used to be a very important part of the diet in Kenyan tribes. It was the universal drink during ceremonies since it could be drunk by both adults and children. It was the common drink during circumcision ceremonies, weddings, dances, and communal labor. It also used to be part of fines imposed on a woman who had wronged other women in a particular community. The most important quality attributed to uji was its ability to increase production of milk in new mothers, who were forced to drink large quantities. Also, it was very important for circumcision initiates during the healing period. It was believed to quickly bring back the normal blood level and compensate for blood lost during the operation. Ogi, another acid-fermented cereal that is traditional in Nigeria, is served to sick and convalescent people because it can be easily digested.

Pulque is the national drink of Mexico where it was inherited from the Aztecs. Pulque, made by fermentation of the juice of Agave, has a very special place in the diet of peasants in the poorest semiarid areas. Agave is the only plant that can grow in the poor soil with the severe shortage of water. For the people in these areas, pulque is a major source of nutrients. The middle-class also consumes pulque on birthdays, at weddings, on picnics, and as an accompaniment to local foods. It is consumed as a low-alcohol beverage and as a nutritional supplement because of its content of vitamins and protein. Medicinal qualities have also been attributed to it by tradition, and it is consumed as a medicine for gastrointestinal disorders, anorexia, asthenia, renal infections, and decreased lactation.

Probably the most well documented fermented food is sour milk. In his 1911 book, The Bacillus of Long Life, Loudon Douglas says, “In Bulgaria, for example, it is stated that the majority of the natives live to an age considerably in excess of what is recognized as the term of life amongst Western nations, and inquiry has shown that in the eastern part of Southern Europe, amongst a population of about three millions, there were more than three thousand centenarians found performing duties which would not be assigned to a man of sixty-five years of age elsewhere. It is quite common to find amongst the peasants who live to such a large extent upon soured milk, that they frequently live to be 110 and 120 years of age.” Also, there is “not the same tendency to the mental decay which is so prominent and sad a feature amongst Western nations”.

He later goes on to state, “The liver and kidneys are the natural guardians of the body against the toxins we are speaking of, and frequently they are over-strained; the soured milk treatment greatly lightens their load. In malignant diseases of the stomach, soured milk will frequently be retained when all other foods are rejected. In cases of neurasthenia and gout it has also proved of value, and in the “run-down” condition which is so common in middle life. Chronic diarrhea and certain forms of constipation have in numerous instances yielded to the treatment, the whey culture being usually found the most suitable. Then, in some forms of anaemia, the lactic acid cultures have proved most successful, and, as a means of rendering the gastro-intestinal tract aseptic previous to operations, it has proved of considerable value.”

It was the opinion of Loudon Douglas (1911) that a lot of diseases that commonly call for a visit to the doctor would be cured by eating more sour milk and the future of the health of people was looking optimistic.

References:

- Douglas, Loudon, M. 1911. The Bacillus of Long Life. WC; Edinburgh: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

- Shurtleff, Wiulliam & Aoyagi, Akiko. 1983. The Book of Miso. 2nd edn. Tenspeed Press, Berkeley.

- Steinkraus, Keith, H. editor. 1996. Handbood of Indigenous Fermented Foods. 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker, Inc. NY.

- Zeffertt, Wendy. 1999. Cultured Foods. Hyland House Publishing Pty. Ltd.