We don’t eat barley, wheat, rye, oats and soybeans raw, they are indigestible that way. Within them and other grains, seeds and legumes, there are substances that stop the nutrients that are stored for growth from spoiling. This is a bit like the preservatives we add to food to keep it from going off. It is how the seeds survive until conditions are correct for growth; their survival mechanism.

Many enzyme-rich raw foods also contain enzyme inhibitors. This is easiest seen with grains, nuts and seeds, which contain both food for the growing plant and enzymes to process this food. Grains and legumes contain phytic acid, an insoluble compound of phosphorus and inositol which binds minerals such as calcium, zinc, magnesium and iron to make them unavailable. Cooking partly deactivates the enzyme inhibitors but does not deal effectively with phytic acid. Cooking also destroys the enzymes themselves. Although enzymes require warmth for optimum activity, they are destroyed by heat as strong as cooking.

Many enzyme-rich raw foods also contain enzyme inhibitors. This is easiest seen with grains, nuts and seeds, which contain both food for the growing plant and enzymes to process this food. Grains and legumes contain phytic acid, an insoluble compound of phosphorus and inositol which binds minerals such as calcium, zinc, magnesium and iron to make them unavailable. Cooking partly deactivates the enzyme inhibitors but does not deal effectively with phytic acid. Cooking also destroys the enzymes themselves. Although enzymes require warmth for optimum activity, they are destroyed by heat as strong as cooking.

These inhibitors that stop plants’ food from spoiling or being used up, not only make the enzymes unavailable to us when we eat the seeds (making such foods difficult to digest), but they can also interfere with the digestion of other foods. Soy beans and nuts are said to have the highest levels of these inhibitors. Just as in other areas of nature, where the first step in germination comes after rain, the first step to deactivate the inhibitors is absorption of water – the water content needs to come up from approximately 12 per cent to 45 per cent. This happens to a certain extent while the grain is cooking in water, but it is far more effective to soak the grain.

A variety of fermentation processes have been used with cereals to increase digestibility, palatability and shelf life. Fermentation produces a strong acidic flavour, increases protein digestibility, and relative nutritional value. Fermentation can also reduce cyanide toxicity in cassava and sorghum, trypsin inhibitors in soybeans, and the antinutritional character of phytate and tannins. The fermentation process provides optimal pH conditions for degradation of phytate.

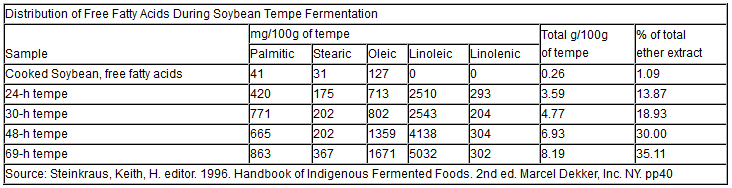

Soy beans are an excellent source of lecithin, essential for the correct metabolism of fats and cholesterol, and of the essential fatty acid, linoleic acid; they are excellent sources of phyto-oestrogens. Fermentation also is reported to convert the harmful phytic acid in soy beans to useful phosphorus and the B vitamin inositol. Also, the action of bacteria, yeasts and enzymes during fermentation converts the trypsin inhibitors and other undesirable compounds to harmless substances.

In scientific studies of fermented cereals the following has been stated:

- The lactic acid fermentation process has been reported to improve the in vitro protein digestibility of nontannin cereal grains.

- Phytate was shown to be completely hydrolyzed after fermentation of germinated white sorghum and, as a result, the amount of soluble iron was found to be strongly increased.

- Protein digestibility was reported to increase from 47% to 73% after lactic acid fermentation of whole-grain sorghum.

- Over a 9-month period, consumption of acid-fermented gruels reduced the incidence of diarrheal episodes in a group of school children; because these foods can be easily digested.

- The growth of rats fed fermented wheat product improved significantly over those fed unfermented wheat, there is an increase in availability of lysine during fermentation.

- A feature of many of these fermentations is that they are capable of improving the digestibility of a raw material and at the same time destroying factors that are toxic, or at least those that might inhibit digestion.

References:

- Subcommittee on Nutrition and Diarrheal Diseases Control, Subcommittee on Diet, Physical Activity, and Pregnancy Outcome, Committee on International Nutrition Programs, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. 1992. Nutrition Issues in Developing Countries. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Steinkraus, Keith, H. editor. 1996. Handbook of Indigenous Fermented Foods. 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker, Inc. NY.

- Whitney, E.N. Rolfes S.R. 1993. Understanding Nutrition. West Publishing Company. MN.

- Zeffertt, Wendy. 1999. Cultured Foods. Hyland House Publishing Pty. Ltd.